Alice Glasnerová

Blogs:

2017

Thank you, Senator McCarthy: 18 Aug, 2017

Noel Field, soviet spy: 10 Sept, 2017

The

hunting dog finds a scent: 30 Sept, 2017

My past ghost: 24 Oct, 2017

Two worlds: meeting Alice for the first time: 26 Nov, 2017

2018

The London connection: 14 Feb, 2018

Stepping into the shadows: 13 March, 2018

Return

to the land of milk and honey: 22 April, 2018

Return to Czechoslovakia: 7 June, 2018

Dual

heritage: 18 June, 2018

Zilina, then and now: 1 July, 2018

A fateful triangle: Erwin, Noel Field and Alice: 29 Aug, 2018

Friends forever: 23

Oct, 2018

Lost luggage: 6 Nov, 2018

Questions of right and wrong: 20 Dec, 2018

2019

Letters from Alice: 26 Jan, 2019

A tale of two photographs: 1 March, 2019

In her father’s steps she trod: April 17, 2019

Prison visit: May 21, 2019

Cartoons and correctness: May 27, 2019

Visiting the dead: June 10, 2019

Alice in the archives: June 21, 2019

Dislocated worlds: May 12, 2019

Au revoir and not good-

Bienvenida Espana: 8 September 2019

Bullfighting in Albacete: 9 September 2019

Benicasim -

Surrounded by danger: 21 September 2019

Arrivals and departures: 29 September 2019

A place of execution (A cold afternoon): November 29, 2019

Seventy years on: 4 December 2019

Windows into the past: 10 December 2019

2021

Munich revisited: February 28, 2021

Will there be a Holocaust museum in Prague?: October 10, 2021

Statue wars: October 14, 2021

Transitional objects: October 21, 2021

My blogs

Dislocated Worlds

May 12, 2019

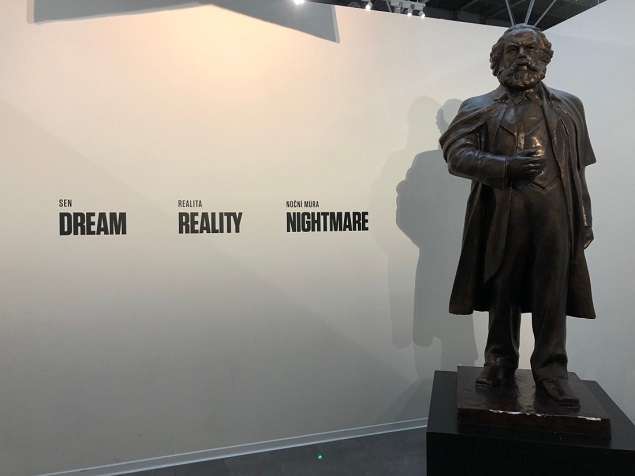

Entrance to the Museum of Communism, Prague

Last week on the way to my language class I spied a tobacconist on the opposite side of the street and, as I needed some more tram tickets, decided to cross over. It was a main road with two tramlines going down the middle. The pedestrian crossing sign showed the red man standing still, but there was no traffic coming. I did notice the policeman on the opposite pavement, but decided to cross anyway. This was a mistake. I had half expected a bit of a telling off, but I didn’t expect to be told I had committed a traffic violation and was to be fined 2000Kc! I didn’t even know it was possible for pedestrians to commit traffic violations.

The conversation that ensued proceeded in a mixture of Czech and English. I wanted him to understand me but thought my chances were better the less Czech I could speak. I explained I was English, that I hadn’t realised it was not allowed, that I was sorry and would never do it again, that I didn’t have 2000Kc (I certainly had nowhere near that on me). He started to relent and said that this once he would just give me a warning, I was full of gratitude and promised never to do it again. For the rest of my walk to school, I stood obediently at every pedestrian crossing, even in front of completely empty roads.

I was reminded of an incident in the USSR when I was there as a student and had set off across the road in Leningrad when, again, the red man was on the crossing sign. An irate, gun wielding policeman had insisted I return to the kerb I had left, even though I was three quarters of the way across. Jaywalking is obviously a habit I have had a long time, learned from my mother, who continued to do it into her late eighties with no adverse consequences. I think we have always both viewed pedestrian crossings as guidance, to be used only when necessary, leaving it as a matter of personal judgement. Some countries take my view to an extreme – Sicily or India, for example, where everybody just crosses as and when they please, cows included, and the rest of the road users keep their wits about them and navigate around them.

Adherence to rules, even those that are unnecessary, is a particularly Soviet habit and although the Czechs (in my brief experience) now view their communist era with horror, certain habits still linger. I have been here just over a week and am finding that researching and thinking about those decades of communist rule raises many interesting questions. One of my earliest visits was to the Museum of Communism, the very name placing it securely in the past as history, dead and buried. For many of the visitors crowding round the various exhibits, it definitely was in the past, they were far too young to remember, and even my young Czech teacher had not heard of the show trials of the 1950s. The emphasis in the Museum is entirely negative, anyone going round would assume that the USSR had schemed from the start to impose an authoritarian regime on the unsuspecting Czechs. That may be true by the 1950s, but in the beginning there was a genuine belief in the ideals of communism. Czechoslovakia was one of the few countries where the communists were a regular legal party before the war. Even in 1968 people were not against communism per se, they wanted communism “with a human face”. It was the USSR’s response that made them realise that this was an impossible dream.